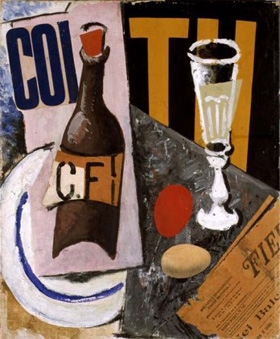

Ardengo Soffici, Still life with red egg (1914).

After a critical review that Soffici wrote on the futurist exhibition in Milan (1911), Fillippo Marinetti and other futurists cornered him at a café in Florence. Later they turned out to be united in their admiration for Mussolini.

Free download of Living Dangerously. A Biography of Joris Ivens

This is the first book to survey the entire career of Joris Ivens, a prolific documentary filmmaker, who worked on every continent except Antarctica over the course of over six decades.

'The best book written on Ivens' (Prof. Ian Buruma, Bard College, Annandale (NY); former chief editor of The New York Review of Books).

'An essential addition to the literature on the documentary in English.' (Prof. Brian Winston in Viewfinder, London).

More on Joris Ivens, also in English: continue...

_________________________________________________

THE AVANT-GARDES ADAPTABILITY...

By Hans Schoots - Close Up 16: Schriften aus dem Haus des Dokumentarfilms (Stuttgart/Konstanz 2003) - The German filmmaker Walter Ruttmann and the Dutch dealer in photographic

equipment Joris Ivens met for the first time in the fall of 1927. At the time

Ivens was living in Amsterdam and had gone to Berlin to invite Ruttmann to

visit the Dutch Filmliga, an organization promoting film art of which Ivens

was a member of the board. On November 19 of that year, the German avant-garde

artist did indeed give a lecture in Amsterdam's Centraal Theater, showing

his abstract films OPUS 2, 3 en 4 for the first time in the Netherlands.

Speaking about his first encounter with Ruttmann, Ivens later said: 'From

our perspective in faraway Holland, Ruttmann was an artistic giant, but when

I saw him at close hand, wrestling with an old, poorly equipped camera, and

limited by a lack of craftsmanship, I realized that from a technical point

of view I was more than his equal.' This was a slight exaggeration. At that

time Ruttmann had owned a Debrie camera for years (between the wars a quality

outfit for any documentary filmmaker), he had developed his own animation

equipment , and above all: he had just finished his masterpiece: BERLIN, DIE

SINFONIE EINER GROßSTADT. Ivens had indeed received an education in

photographic and film technique at the Technische Hochschule at Berlin-Charlottenburg

between 1921 and 1924, but in 1927 he had not yet completed a film, and in

the beginning he would work with a Kinamo handheld 35 mm camera that was intended

for the use of wealthy amateurs.

Nonetheless, his visit to Ruttmann encouraged Ivens to make his first complete

film: DE BRUG (THE BRIDGE). Although Ivens valued the surrealism of the French

avant-garde, the new fiction films from the Soviet Union and the pure abstraction

of Richter, Eggeling and the early Rutttmann films, he was much more inspired

by the Neue Sachlichkeit of BERLIN, DIE SINFONIE EINER GROßSTADT. Ivens

was a matter-of-fact technician with a great belief in technological progress

and a natural orientation towards visible reality, and this film showed him

how to become an innovative artist. In DE BRUG he filmed the

reality of a modern industrial product according to the aesthetics of 'rhythm

and movement', the standing expression in the Dutch Filmliga.

Ruttmann also became the great example for writer Menno ter Braak, the leading

theoretician of the Filmliga. For him and his followers, BERLIN exemplified

true cinematic art. The magazine Filmliga wrote: 'Here, for the first

time, one could probably risk using the words "lasting value".'

It is no coïncidence that the first book on Ruttmann was published in

the Netherlands. In this modest 1956 publication, Walter Ruttmann en het

beginsel (Walter Ruttmann and the Principle), film critic A. van

Domburg explained that the artistic credo, as expressed in Ruttmann's work

as a whole, represented the definitive truth on film art. He still considered

Ruttmann 'the soundest filmmaker in the world'.

On first sight, the story of Walter Ruttmann and Joris Ivens between the

wars can be summarized in the following manner. In the twenties they were

part of the international avant-garde movement; the work they did in the late

twenties belonged to the school of Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity. They

both had intensive contacts in the artistic circles of several countries:

Ruttmann was an active participant in the avant-garde movements in Germany

and France and also worked in Italy. From his base in Amsterdam, Ivens regularly

visited artists in Berlin, Paris and, from 1930, Moscow. It was partly due

to Ivens's many international contacts that, apart from Ruttmann, other leading

figures in the international avant-garde, people like Hans Richter, Germaine

Dulac, René Clair, Alberto Cavalcanti, Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod

Pudovkin, made appearances at the Filmliga in Amsterdam.

Then in the thirties, Ruttmann and Ivens suddenly went completely different

ways. The former worked in Nazi-Germany from 1933, the latter became a member

of the Communist Party in 1931 and worked in the Soviet Union for three years

between 1931 and 1936. Ruttmann died in 1941, and in the forty-eight years

that Ivens outlived him, he never uttered a word about Ruttmann's work from

the thirties. Ivens must have missed most of it, but then, he never seems

to have wondered about it either: his former role model had gone over to the

enemy camp.

This résumé however does not do justice to the complexity of

what happened between the world wars, to the avant-garde, to documentary film,

or to the lives and work of these two filmmakers.

Avant-garde: social change by aesthetic means

Avant-garde remains a problematic term in the history of cinema. Illustrative

is the case of German expressionism in film, which, as Thomas Elsaesser argues,

was a use of stylistic elements to give industry an artistic image rather

than an artistic movement as such. Between this one extreme and the 'pure'

independent film, which is considered to be high art, lies the gray area where

Soviet innovators like Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin operated within

the film industry of their country, and of French avant-gardists like Alberto

Cavalcanti and Marcel l'Herbier, who alternately worked within and outside

of the established industrial system.

Still, the term avant-garde remains useful, especially to indicate those experimental

filmmakers who considered themselves part of the avant-garde movement that

existed in the traditional arts as well, and that several of them originated

from, like the painters Walter Ruttmann and Hans Richter.

The cinematic avant-garde had its variations, stretching from the surrealistic

dream images of Germaine Dulac to the steel constructions of Ivens's DE BRUG,

just as in painting the mystic realism of Marc Chagall went with the stern

modernism of Piet Mondrian. The artistic avant-garde nevertheless had some

important unifying characteristics. First of all there was the general conviction

that new art had a task in creating a new society. Starting from aesthetics,

it would lead the way to a better world. Expressionists and surrealists thought

this could be done by fundamentally changing the mentality of the individual,

whereas futurism, constructivism and Neue Sachlichkeit celebrated a new industrial

future and tried to give it form. As Peter Bürger wrote in Theorie

der Avantgarde: 'The avant-gardists consider it to be the dominating characteristic

of art in bourgeois society that it is divorced from the practice of social

life. […] Therefore, the avant-gardists intend to liquidate art - liquidation

in the Hegelian sense of the word: art should not simply be destroyed, but

should be integrated into social practice, where it would continue to exist

in a different form. […] They try, starting from art, to organize a new

social practice.'

An unending flow of militant manifestos and pamphlets, an urge for sensational

public manifestations and, of course, a permanent desire to cross all boundaries

in art itself were expressions of a generally felt radicalism among the avant-garde.

Despite the regularly occurring sectarian confrontations that are by nature

a part of radicalism, the universal ambitions of the avant-garde went together

with interdisciplinary thinking and a strong feeling of international unity:

artistic disciplines became interconnected in the service of a greater vision.

Numerous contacts developed between filmmakers, painters, writers, photographers,

architects and designers, and many of them became active in several disciplines.

From the beginning this desire to change the world by aesthetic means, to

integrate art and social practice, did lead to a tendency to link up with

political and economic powers. Initially the idea seems to have been: as long

as the world is turned upside-down it doesn't matter how it is done.

From 1915 the Italian futurists around Filippo Marinetti supported Benito

Mussolini, hoping that in this way they would be able to realize their own

visions of a new world. In 1919 Marinetti became a member of the Central Committee

of the Fascist party. With similar expectations, the Russian futurists took

the side of the Bolshevik party in 1917. In Germany artists from the Dada

and expressionist movements, like George Grosz and Erwin Piscator, joined

the communists or radical socialists after the revolution of 1918, and the

French surrealists led by André Breton became members of the French

Communist Party in 1927. In the meantime other - and partly the same - avant-gardists

designed modern buildings, industrial products and advertisements for capitalist

enterprises and democratic governments, just as Walter Gropius did at the

Bauhaus and in the United States.

At this early stage, the avant-garde seemed to be compatible with fascism,

communism and liberal capitalism. National-socialism would follow.

A mixture of left and right

Despite all their political connections, avant-garde artists kept some kind

of political innocence for quite some time. They cherished the illusion that

they would be able to play a decisive role as equal partners of the political

'avant-gardes' in an alliance between new aesthetics and revolutionary politics.

In a process of years, the Italian and Soviet regimes in particular - the

latter with considerable international influence through the Communist International

- would succeed in making art serve their own ends. A section of the artistic

avant-garde came to accept the primacy of politics, in the continuing belief

that, despite everything, a common ground with the political leadership still

existed. In this sense, the events of 1932 and 1933, when socialist realism

became party doctrine in the Soviet Union and Adolf Hitler came to power in

Germany, were not the beginning of a new era for the avant-garde, but rather

one more step in a voluntary process of politicization that had been going

on since World War I.

In the second and third decade of the twentieth century, different political

and economic connections did not preclude contacts between artists. Russian

and Italian futurists continued their hearty relationships for a time, despite

the fact that they had linked up with communism and fascism respectively.

From 3 to 7 September 1929 representatives of at least ten countries met in

harmony at the International Congress for Independent Film in La Sarraz, Switzerland,

the most important international film avant-garde gathering of the decade.

Among them were Ruttmann and Richter from Germany, Eisenstein from the Soviet

Union and Dutch filmmaker Mannus Franken on behalf of the Filmliga. Enrico

Prampolini, who represented the cineclub movement in Italy, announced that

the fascist government would reorganize the movement and put it under the

leadership of Marinetti. Government film production would from now on be under

the aegis of futurism and have 'absolute independence', he further declared.

Nobody present seems to have questioned this premise.

In the artistic circles to which Ivens and Ruttmann belonged, left and right

were mixed in the twenties. Ivens, despite his own leanings to the left, collaborated

with the infamous Dutch Mussolini-admirer Erich Wichman in 1927-1928 on a

film called DE ZIEKE STAD (THE SICK CITY). The two had been friends since

the early twenties when they both stayed in Berlin. Wichman was the anti-bourgeois

artist par excellence and a popular figure among Dutch avant-gardists.

In Italy he had been in contact with Marinetti.

According to Wichman's scenario

for DE ZIEKE STAD, the film was to show that Amsterdam was doomed unless rightist

anti-democratic measures were taken. Ivens seemingly only shot some (now lost)

fragments of the never finished film. The Dutch expressionist poet Hendrik

Marsman, who had been among Ivens's intimates since his Berlin days, also

sympathized with Mussolini for a time. He was the author of the words that

became famous in Holland as an expression of the feelings of the avant-garde,

regardless of political boundaries: 'Spectacular and moving is the life I

want! You hear me, father, mother, world, charnel house!'

Among Dutch artists and intellectuals who wanted to remodel the world according

to their new aesthetic criteria, a tendency existed towards a vague, anti-democratic

elitism: of course the new world would not result from the decisions of the

gray majority, it would result from the power of enlightened minds.

Walter Ruttmann, in his turn, was a member of the board of honor of the left-leaning

Volksverband für Filmkunst, together with the communist theater director

Erwin Piscator. In 1931, two years before he cooperated on the national-socialist

film BLUT UND BODEN, Ruttmann still considered working for the Mezhrapbom

Studio in Moscow. That this did not materialize, seems to be due more to Moscow

than to Ruttmann. In the same year Hans Richter went to Mezhrabpom, to work

on his unfinished METALL, about the repression by Stahlhelm troops

of a steelworkers' strike in the German town of Henningsdorf.

Even in the thirties political contradictions did not always weigh very heavily.

Right after making a promotion film for the Dutch capitalist electronics company

Philips, Joris Ivens rushed to Magnitogorsk in the Urals to film an ode to

socialist industry. Actually, Richter had also just made a film for Philips,

called EUROPA RADIO , before going to the Soviet Union for METALL. Pragmatic

considerations and self-interest must have played a role in all this. There

was however also an underlying feeling that made these seemingly incompatible

activities permissible even in terms of content.

The age of industry

Now that the era of great ideologies lies behind us, we can zoom back and

look at the years between the world wars from some distance and see that liberal

capitalism, communism, fascism and national-socialism, despite all their differences,

do have an important thing in common: a belief in progress through industrialization

and mass production.

In his youth, Joris Ivens learned from his broadminded liberal father Kees

Ivens that technology was the key to social progress. His father was an enthused

advocate of this vision in the Dutch city of Nijmegen. At the end of the nineteenth

century, the ancestral home was one of the first local houses where electricity

and other modern innovations were introduced. Ivens senior also initiated

the building of a large steel bridge over the Waal River and other modern

projects.

One could say that communism drove the liberal belief in progress to its limits,

just as Karl Marx developed his economic theories, based on 'the development

of the forces of production', partly from those of the liberal Adam Smith.

Lenin in his turn simply declared that 'Communism is Soviet power plus the

electrification of the whole country'. In his book The Fellow Travellers.

A Postscript to the Enlightenment, David Caute argued that much of the

attraction of the Soviet Union for artists and intellectuals from the West

derived from the feeling that Soviet communism 'signified a return to the

eighteenth century vision of a rational, educated, scientific society based

on the maximization of resources and the steady improvement (if not perfection)

of human nature…' Other authors, like the French historian François

Furet, also analyzed communism as an extreme variation on the ideas of the

Enlightenment. When Benito Mussolini was still a radical socialist, he could

be placed in this same tradition, and elements of this thinking remained during

his fascist period. In the twenties, Mussolini stressed the need for modernization

of the backward Italian society, using catchwords like 'dynamic', 'vitality'

and 'youth' that had much in common with the terminology of the futurists.

Adolf Hitler used a highly symbolic Soviet term when he introduced his Four

Year Plans (although the Soviet Union had Five Year Plans). Although economic

development in Germany was probably less planned and centrally-led than the

words 'four year plan' suggest, they still express the Nazis' desire to build

up a powerful, modern economy. And contrary to Stalin, they already had one

of the world's most developed economies at their disposal.

In the debate on cinema in Nazi Germany, several authors have pointed at the

reality of consumerism in Nazi Germany and the glorification of industry in

Nazi thinking, partly influenced by 'reactionary modernists' or 'conservative

revolutionaries' like Ernst Jünger, who saw industry as an essential

characteristic of the new society. Whereas the basic idea of Marxism was that

human progress is an unending struggle against nature, Nazi ideology

played on popular fear of an uncertain, ever-changing future by suggesting

that tradition and unspoiled nature would remain uncompromised despite modern

technology and mass consumption. But 'when ideology came into conflict with

economic facts, it was ideology that had to give way'.

Maximum industrial development was of course also a practical precondition

for the realization of other Nazi goals: an efficient war industry to conquer

Lebensraum and a strong German economy that was to be the motor for

a Großraum Europa, once conquered. Racism and the modern finally

met in Auschwitz and other camps, where the Jews were to be destroyed by rational,

industrial means.

'The cinematic expression of the twentieth century production

line manufacturer'

In the thirties Joris Ivens and Walter Ruttmann, although working under

communism or nazism, in many ways kept to the ideas of Neue Sachlichkeit,

which, like futurism and constructivism, idealized modern life and industrial

society, striving to integrate its spirit into the arts and, inversely, hoping

to aesthetically give form to this new society of industry, speed and dynamism.

Technology was progress, technology was beauty - it was an ideal and an aesthetic

practice in one.

Despite the opposite political directions they took, their work continued

to show many similarities well into the thirties. This applies first of all

to their films concerning industry and new technology. For Ivens these were,

starting from 1930: ZUIDERZEE/NIEUWE GRONDEN (NEW EARTH), PHILIPS RADIO, CREOSOOT

(CREOSOTE), PESN O GEROJACH (SONG OF HEROES) and BORINAGE. Ruttmann's films

in this field were ACCIAIO, METALL DES HIMMELS, SCHIFF IN NOT, MANNESMANN,

IM ZEICHEN DES VERTRAUENS, WELTSTRASSE SEE-WELTHAFEN HAMBURG, HENKEL-EIN DEUTSCHES

WERK IN SEINER ARBEIT, DEUTSCHE WAFFENSCHMIEDEN and DEUTSCHE PANZER.

How much they had in common becomes clear when we concentrate on a more or

less representative selection from these films: the Ivens films PHILIPS RADIO

(1931) and PESN O GEROJACH (1933) and the Ruttmann films METALL DES HIMMELS

(1935), MANNESMANN (1937) en DEUTSCHE WAFFENSCHMIEDEN (1940). At the time

Joris Ivens called his PHILIPS RADIO 'the cinematic expression of a, rather,

the twentieth century production line manufacturer'. PHILIPS RADIO

was not a socially critical film, it expressed what Marxists would call a

'classless' view of society. Nowhere in this film could any sign be found

of Ivens's communist beliefs, on the contrary, he emphasized the things that

linked him to capitalism: pure avant-garde aesthetics confirmed and

stressed the beauty of the industrial process. Later, Ivens sometimes suggested

that PHILIPS RADIO needed to be seen as an anti-capitalist film, but this

view is hard to uphold. The sequence that he invoked for this purpose, the

one that shows how arduous the work of glassblowers is, does not say anything

for or against their situation. The workers in Ivens's socialist PESN O GEROJACH

had to work a lot harder under worse circumstances and nevertheless these

were presented in a positive way, whereas Philips's glassblowers were shown

in a neutral mode. No wonder that most critics in Holland found that, although

Ivens had made a beautiful film, it lacked interest in working people. In

fact, the sequence on the glassblowers gave first of all a sympathetic view

of these workers because of their impressive skills, with the professional

peculiarity that, while blowing, their cheeks became extremely swollen: like

Dizzie Gillespie playing trumpet.

Even Ivens's PESN O GEROJACH could, despite the obvious communist propaganda,

be read as a great, archetypal ode to industrialization in general. This was

also recognized at the time by his ideological rivals at the main Dutch social-democratic

newspaper Het Volk. Its critic called PESN O GEROJACH 'the most beautiful

symphony on labor ever made' , that is, not of manual labor as such, but of

labor for the construction of an industrial society. A main theme of the film

was that peasants should leave their backward past behind for work in industry.

It has been rightly argued in various ways that Walter Ruttmann, especially

in his industrial films, kept to the same stylistic ideas that he had cherished

in the late twenties. Indeed, Ruttmann too could have called his MANNESMANN

'the cinematic expression of a, rather, the twentieth century production

line manufacturer'. Only one shot of a flag with swastika betrayed to audiences

that this film had been made in a factory in Nazi Germany, and some innocent

images showing the beauty of the forests, refer to that other aspect of Nazi-ideology:

the glorification of unspoiled nature. METALL DES HIMMELS, in unequivocal

avant-garde aesthetics, tells us that steel is useful everywhere, from kitchen

to battlefield. But which army, and whose battles were shown? Visually it

all remained abstract, only this time the commentary linked some of the images

to German revanchism. It is significant that, eleven years after the end of

World War II, Dutch author A.van Domburg could discuss METALL DES HIMMELS

in his book Ruttmann en het beginsel without any reference to a possible

political meaning.

DEUTSCHE WAFFENSCHMIEDEN, with its 'soldiers' fighting the same struggle on

two fronts, in industry and on the battlefield, brings to mind Ernst Jünger's

'reactionary modernist' vision of future society as described in his book

Der Arbeiter (The Worker): a society organized as an army, in

which workers are soldiers and soldiers workers, in which state and factory

are integrated like a beehive, and everybody is ready for battle. Just as

in Ruttmann's other war propaganda-film DEUTSCHE PANZER, however, the aesthetics

of Neue Sachlichkeit did not combine very well with the film's political aims.

Ruttmann's usual abstract images of industry and his lack of interest in the

workers' and soldiers' emotions cannot have had much propaganda impact on

the audience. Just as Martin Loiperdinger writes in his analysis of the film:

'All enthousiasm is lacking', and:'Thus, as an artistic end in itself, formalism

comes between those who commissioned the film and the audience'. His conclusion:

'In METALL DES HIMMELS and DEUTSCHE PANZER Neue Sachlichkeit and National-Socialism

did not become very close after all,' is not, however, fully satisfactory.

Even if ineffective, these Ruttmann films remain propaganda. They at least

try to express a political view and the heroic workers' and soldiers' faces

suggest that Ruttmann was doing his best. In earlier work, such as his city

films on Stuttgart and Düsseldorf, he had been more succesfull in combining

his modern style with less modern demands of the prevailing ideology. Rather

than showing an incompatibility with Nazism, his 'war-films' seem to expose

the difficulty he faced in uniting various aspects within Nazi-ideology.

The Neue Sachlichkeit we find in films under liberal capitalism, Nazism and

communism, emphasizes the similarities in social systems that were so different

in many other ways. Industry, mass production, 'the twentieth century

production line' and the speed of life were a dominating force in all of them.

Authors under commission

In the thirties Ruttmann and Ivens both made their films under commission

from a great variation of institutions. Ivens worked for, among others, the

Dutch social-democratic construction-workers union, the Philips company, the

European timber industry, the Mezhrabpom Studio in the Soviet Union, several

communist-led committees in America, and the United States Department of Agriculture.

Ruttmann worked for, amongst others, a studio in Mussolini's Italy, the German

Advisory Board for the use of steel, the German Lifeboat Association, the

Mannesmann, Bayer and Henkel companies, the Warehouse Association in the port

of Hamburg, several German city councils and the German state. Most of these

ordered their films at Ufa Werbefilm, where Ruttmann was employed from 1935.

In Claiming the Real Brian Winston writes - referring to John Grierson's

definition of documentary as 'the creative treatment of actuality' - that

the main aim of his book is 'to argue that running from social meaning is

an inevitable structural flaw in any film which creatively treats actuality

in the name of public information, education, social purpose, or what you

will - whoever makes it. That is why wherever and whenever such work has been

undertaken it has almost always reproduced on the screen the facile attention

to surface detail, and little else, which characterizes the Griersonian oeuvre.'

He supports his proposition with, amongst other things, a convincing comparison

of British, American, German and Soviet documentaries, which turn out to possess

in many ways the same flaws that he notes in Grierson's. An obvious reason

for this is, of course, that the filmmaker was subservient to whoever commissioned

his film and tended to leave out things the commissioning person or body objected

to.

Nevertheless, many of these documentarists remained convinced of their own

independence, and even those who commissioned the films spoke in similar terms.

The Italian representatives at La Sarraz in 1929 could announce in one breath

that the fascist state was going to reorganize their cineclub movement and

that state filmmaking would have 'absolute independence'. In the twenties

Walter Ruttmann himself had set his hopes on the state for defending independent

cinematography, but he became disappointed by the inactivity of the German

government. In another Germany, in 1942, the Reichsfilmintendant Dr.

Hippler left no doubt that 'Gesamtplanung' was necessary, while immediately

adding: 'There is no other artistic discipline, where it is more difficult

for the loner, the avant-gardist, the pioneer, the man with new ideas, to

succeed, than in film. But within film, he doesn't have better chances anywhere

else than in Kulturfilm.'

When Joris Ivens went from Moscow to the United

States in 1936, he got orders from the Mezhrabpom Studio 'to stimulate independent

film production and the film movement for the popular front', in which 'independent'

and 'popular front' were considered almost interchangeable terms. 'Popular

front'-organizations were generally led by the communist party, sometimes

with Ivens himself as its main representative. The conviction of filmmakers

of being independent had its roots in the avant-garde of the twenties, which

wanted to make film into art by becoming independent of the entertainment

industry. Even in 1942 Dr. Hippler kept this feeling alive by making a

sharp distinction between Kulturfilms and fiction films: 'In contrast to the

latter, the great Kulturfilms however were usually the work of an obsessed

and fanatical loner'. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels too saw an antagonism

between the commercialism of 'Rentabilitätsbonzen' and individual

film artists, and wanted to strengthen the position of the latter… by

rigid state control. Filmmakers, especially in documentary, had a false feeling

of independence because those who commissioned their films allowed them to

continue working outside of the entertainment industry. In describing the

position of Leni Riefenstahl in Nazi-Germany, Rainer Rother summarizes this

two-faced situation in the expression 'Autorin im Auftrag': author under commission.

As we have seen before, there is a third side to the matter: filmmakers like

Joris Ivens and Walter Ruttmann actually had many ideas in common with those

who commissioned their films, stretching from a common belief in industrialization

to complete political and ideological agreement. Ivens cherished deep communist

convictions. Ruttmann's case is less clear, as up till now, biographical information

on his life in the thirties is scarce. But information in Jean Paul Goergen's

Walter Ruttmann. Eine Dokumentation, and of course some of Ruttmann's

films, and the content of his initial work on TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, do suggest

that he more or less sympathized with Nazism. This is, as we can now see,

not as contradictory to his avant-gardism as was thought in the past.

The fact remains that 'running away from social meaning' applies to most of

the films from the thirties by both Ivens and Ruttmann, not only because they

were commissioned films, but also because their makers omitted things that

did not fit into their own convictions. In Ivens's PESN O GEROJACH, the 35,000

forced laborers in Magnitogorsk, who had been deported for resisting collectivization

or for practicing their religion illegally, remain unmentioned, although Ivens

admitted knowledge of their presence fifty years later. The complete lack

of a critical note in Ruttmann's war propaganda may just as well have been

caused by his own convictions as by orders from above.

The 'facile attention to surface detail' that Winston points out has another

aspect as well. In the case of Neue Sachlichkeit, special attention to the

surface was not only a matter of superficiality. It also expressed the belief

of Ivens, Ruttmann and others that the external beauty of the modern world

was a result of its inner qualities.

Undermining Neue Sachlichkeit

Despite the continuities, it would of course be one-sided to suggest that

Ruttmann and Ivens went on in the thirties just as before. As the decade passed,

they became more and more immersed in the communist and Nazi worlds they were

part of. Where their modernism lasted, it was in specific variations consistent

with Nazism and communism. On the other hand, in many ways, their modernism

did give way to the 'anti-modern' elements present in both ideologies. One

could add that in liberal capitalism, Neue Sachlichkeit had to adapt to specific

demands too. Its artistic purity was inevitably lost as soon as it tried to

integrate in social practice, wherever it was.

Although in the work of Ruttmann, Neue Sachlichkeit remains prominent until his death in 1941, even in downright war propaganda, there still was also another tendency present in his work from 1933 onwards. The films that Ruttmann was involved in during the first years of Hitler's rule, BLUT UND BODEN (1933) and ALTGERMANISCHE BAUERNKULTUR (1934), were typified by William Uricchio as his 'initiation films': they seem to be meant to prove his loyalty to the new regime. 'In BLUT UND BODEN Ruttmann keeps to his dynamic vision of the city as rhythm, but in his narrative context, this serves as an explicit criticism of urban life - as compared to the extensive images of peaceful country life. This recanting in technical presentation as well as in his extremely positive vision of the city goes for his next city films as well,' writes Uricchio. In accordance with Nazi ideology, Ruttmann tried to show in these films that, although the modern city had become a fact of life, harmony and tradition prevailed.

In communist thinking, industrialization was considered the basis of social

progress. This did not mean, however, that modern art had more freedom under

communism than under Nazism, at least not in the thirties. Stalin needed the

support of the average worker and farmer. Avant-gardism had seldom appealed

to the broad masses of the population in any country. Despite the wishes of

experimental artists to play a role in society, they hardly ever succeeded

in (or were even prepared to try) expressing themselves in a language that

was understood by what one used to call 'the masses'. Although Stalin's turn

to socialist realism may have coincided with his cultural tastes, a more important

factor must have been his need for a culture that could bind a large part

of the population to his regime.

Categorical conclusions on Soviet non-fiction

film in the thirties are impossible, as very little research has been done

on the subject, as far as it concerns the period of the domination if socialist

realism. The aesthetics of Neue Sachlichkeit, as used by Ivens in PESN O GEROJACH,

probably influenced later Soviet-documentaries (Russian: kul'turfil'my) and

newsreels, especially on industrial and technological themes. But even in

industrial films, a narration inspired by fiction film was now demanded, as

Ivens experienced when his PESN O GEROJACH was criticized as being too formalistic.

Mainly influenced by discussions at Mezhrabpom in 1932-1933, Ivens declared

in 1934 that he had gone over to 'socialist realism'. He considered BORINAGE

(1934), co-directed with Henri Storck, to be the turning point. As his other

films of the period 1934-1936 are lost, it is difficult to say how he developed

stylistically in those years. His later work from the thirties, THE SPANISH

EARTH and THE 400 MILLION, made in the Spanish and Chinese wars, were certainly

social realistic documentaries with a political purpose. In SPANISH EARTH

the main subject was, apart from warfare itself, the irrigation of the land

of a relatively primitive agricultural cooperative, shown in a way that expressed

a belief in social and technological progress in the countryside, but in a

cinematic language that had left avant-gardism behind.

His break with avant-gardism in a way was less radical than he himself claimed.

He had made plain (social-)realist films in the twenties too, especially DE

NOOD IN DE DRENTSCHE VENEN (POVERTY IN THE BOGS OF DRENTE, 1929) and several

of the separate parts of his 141 minute trade-union film WIJ BOUWEN (WE ARE

BUILDING, 1930). Almost from the very beginning a social realistic and an

avant-gardistic mode were alternately present in his work.

Ivens has always used avant-gardism in a more pragmatic way than many of his

colleagues. He was a practical man, that is one of the reasons why Neue Sachlichkeit

appealed to him in the first place. Probably more than any other current in

the avant-garde, Neue Sachlichkeit was linked to utilitarian thinking. For

Ivens, it was not a big step to use a different style when social or political

circumstances seemed to require it. He himself had noted critically at an

early stage that the avant-garde remained largely isolated from 'the masses',

and especially in later years of ideological and political escalation, it

must not have been difficult to convince him of the advantages of social and

socialist realism.

Walter Ruttmann was, and stayed, more radical in his avant-gardism than Ivens

has ever been. The utilitarian side of Neue Sachlichkeit nevertheless turned

out to be part of his thinking too. The continuity in modernist content and

aesthetics in the work of Ruttmann, and to a lesser extend of Ivens, went

together with a preparedness to undermine these when it seemed useful.

Despite the smooth development of their work, from the twenties into the thirties,

a fundamental change had nevertheless taken place: starting out as avant-gardists

who wanted to change the world by aesthetic means, they had become 'authors

under commission'. Their art had become an instrument in the service of politics

and economics of the industrial era.

© Hans Schoots. This article (with notes) was published as Zooming out. Walter Ruttmann and Joris Ivens in: Peter Zimmermann und Kay Hoffmann (Hg), Triumph der Bilder. Kultur- und Dokumentarfilme vor 1945 im internationalen Vergleich. Close Up 16, Haus des Dokumentarfilms, Stuttgart / Konstanz 2003.

The book was published after the international film history congress 'Triumph der Bilder' in Berlin, 2000.

Haus des Dokumentarfilms: www.hdf.de